(photo by: Danny Wilcox Frazier)

by Charlie LeDuff —

There they lie, as pretty as you please, stacked in the refrigerators, row upon row like so much bread on a baker’s shelf; the dry goods are stored separately in a nearby pantry.

But there are few takers for the wares on display here at the Wayne County Morgue in midtown Detroit. They are the remains of 269 human beings who go unclaimed, unwanted, and oftentimes unknown. They are in their destitution a macabre barometer not only of the economic times but also a sad reminder of how cold and estranged the human heart has grown.

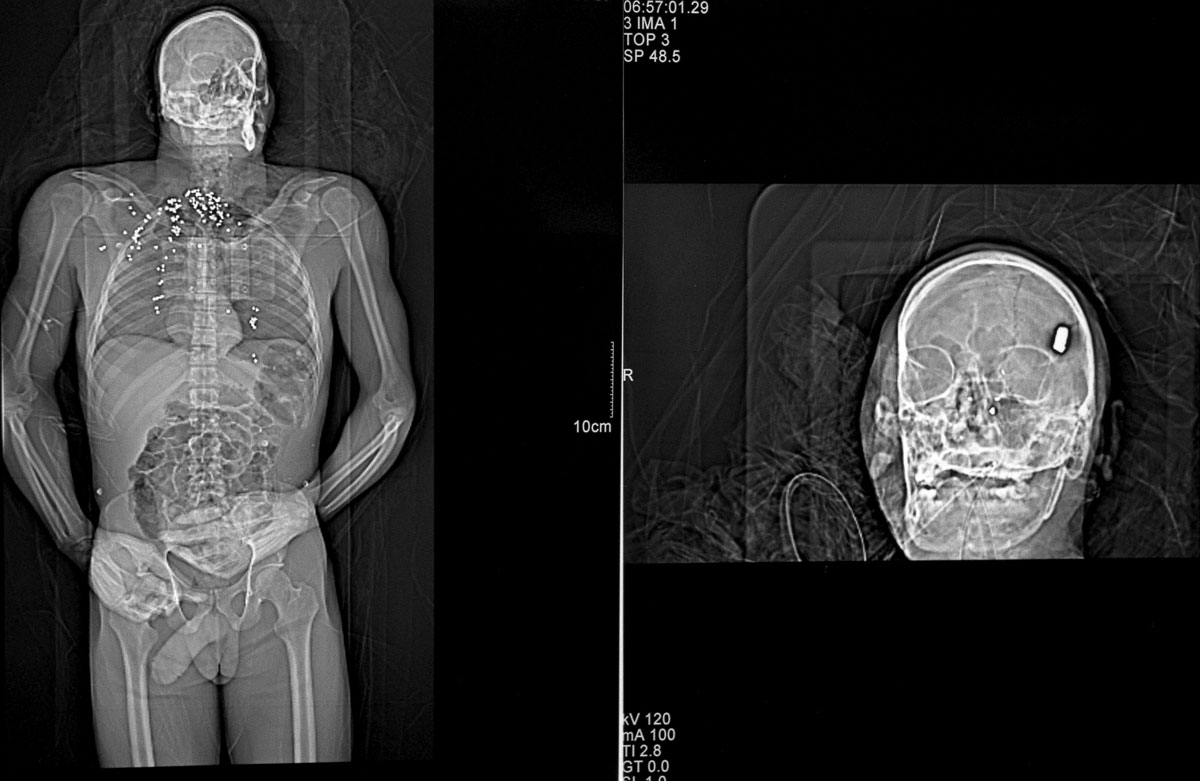

Ninety-six of them are skeletons, and quite a few have been here for years, explained Bill Kasper, chief investigator for the medical examiner’s office. These are the unfortunates whose identities remain unknown. People who were found in various states of misadventure and decomposition.

“But you never know with today’s DNA technology,” said Kasper, a big-hearted death detective. “I’d rather have a body on the shelf to give to a family rather than a pile of dust in an urn.”

That leaves another 173 full flesh and bone bodies on ice; the overflow handled by a tractor-trailer-sized refrigerator in the back parking lot.

Wayne County had the same problem of overcrowding back during the Great Recession when Wall Street collapsed and the City of Detroit went broke. To ease the pressure, the state allowed its county coroners to cremate unclaimed bodies, thus providing a more dignified ending to a life than having one’s corpse perpetually rearranged like a withered cucumber in a vegetable crisper.

Gradually, things improved at the morgue, until the economy went sour. Once again, bodies stack up – another unmeasured consequence of Bidenomics. It is a problem that plagues nearly every American metropolis today, from Chicago to LA.

The backlog of bodies could be dispatched quicker of course, if there were only more money. But that is not the priority of local politicians, who instead give millions of public dollars to the billionaire pizza baron, who in turn builds a million-dollar mausoleum for his parents. The least fortunate get the back of the fridge.

The morgue is the destination for those who died from the unnatural, the unintentional, or while incarcerated. Put another way, the majority of those who get an autopsy are the decomposed, the drug-addled, or the down-and-out. And of course, the homicide victim.

Business is brisk at the Wayne County Medical Examiner. As fast as they can clear them out, in they come. The medical examiner’s office fields 18,000 calls a year and accepts 3,500 customers — officially known as decedents. That’s roughly 10 a day, every day, multiplied by 365.

From the professional experience of Kasper, the relationship between the unclaimed body and its one-time kinfolk generally splits into two categories:

The first might be described as a broken heart. These are the sort of people who had disavowed their relation in life, having been so wounded or wronged by him that they refuse to collect him in death.

“I hear that more often than you know,” said Kasper. “ Stuff like, ‘Eff-him. I want nothing to do with him.’ Really makes you wonder.”

The second type of relationship may best be described as flat-out broken. There are people, who month after month, implore the morgue to keep their loved one for just a little bit longer as they wait for their ship to come in. Like everything else, the price for cremation and funerals has gone up, and people will drag out this layaway plan for months and sometimes years.

Eventually, when shelves get to capacity, Kasper must call the funeral director who will take the body to a crematorium, and then transport the cremains to a mausoleum at Our Lady of Hope cemetery in Brownstown. The state of Michigan picks up the $700 tab.

“It’s a real financial sign of the times,” said Kasper. “People don’t have the money lying around for emergencies. Sometimes the only option, the cheaper option, is to let the taxpayer take care of it.”